8th grade graduating class, Oak Grove School, 1933

A teacher’s influence can have a long reach, even into the next generation. As Ralph Waldo Emerson, America’s finest philosopher, said, “a man’s reach should exceed his grasp or what’s a heaven for?” The word “reach” here expresses hope or ambition, where “grasp” pertains to the practical world of accomplishment. That is, a teacher may have hopes for her students that exceed what she is able to obtain for them, and the students may apply that maxim to their own lives, holding steadfast to a dream even though it is not obtainable.

In 1933, Daisy Palmer was teaching the eighth grade at a one-room country school named Oak Grove northwest of Chandler. The graduation photo--clearly by a professional photographer and doubtlessly paid for by Ms. Palmer, since poor farm kids had no money--shows the teacher and four students. In the background, a floral design may be discerned of the kind popular in family photographs. Often such a backdrop means the subjects have made a visit to the photographer’s studio in town, but not in this case. The students had to be home to help with the farm chores, and the school was seven miles from town. The photographer would have carried the boards for the backdrop with him from town, and Ms. Palmer would have somehow found Sunday-best clothing for her students to wear.

231

8th grade graduating class, Oak Grove School, 1933 Back row: C.R. Miller, Archie Pounds, Ruth Smith Front row: Daisy Palmer and unidentified.

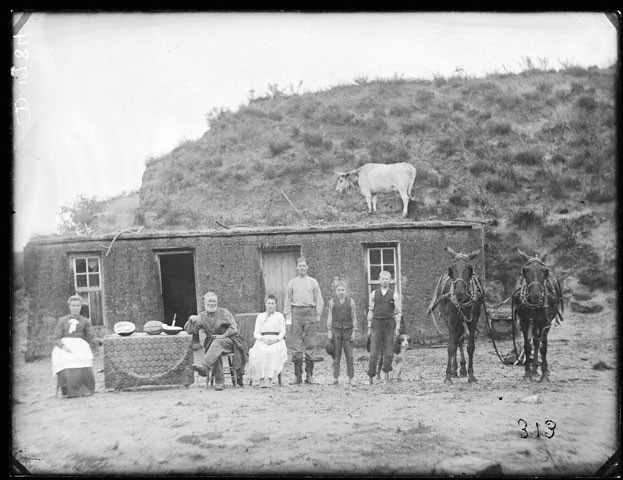

The use of background boards was common practice among rural photographers from the time of the invention of modern photographical technology after the Civil War down to the 1940s, but there are exceptions. One is provided by the brilliant photographer Solomon Butcher who worked with farmers in Custer County Nebraska around the turn of the 20th century. Butcher had the genius to reverse the dependence on backdrops. He made the farm itself the background. It also provided the middle ground and foreground. The usual backdrops were designed to show the family’s success by suggesting the furnishings of a middle-class home. Butcher’s style also included furniture, but he used the real thing. He had his families bring their possessions outside (the homes in central Nebraska were commonly “soddies”--sod houses--too dark inside for a photograph) where he took their picture surrounded by their possessions including the farm, the out buildings, and the livestock.

232

Solomon Butcher, “Sylv Rawling House,” Custer Co. NE, 1886

Still, one would like to know who took the photograph of the Oak Grove 8th grade graduating class. Of professionals operating in the Chandler area in 1933, only one name comes to mind and that is Albert A. Bass, a photographer I only learned about in the course of doing a book on Chandler’s Wright Cemetery. He had a boy named Albert Leo Bass, who was was less than one year old when he died in 1900 and was buried in Wright. Only pieces of his grave stone have been recovered (see below), but the father’s life is well known and complete. In the Wright Cemetery book [see Sources at the end of this essay], I wrote:

The Wisdom of Jesus ben Sirach, better known as Ecclesiasticus, commands, "Let us now praise famous men, and our fathers that begat us" (44:1). The rule is

233

apt for little Albert Leo Bass, for his father was the well known Chandler photographer and puppeteer Albert Alexander Bass (1871-1961), several of whose

Remains of Albert Leo Bass’s stone, used with permission of Sherry Springer

photographs are archived in the Oklahoma Historical Society and many more adorn the homes of people in Lincoln County. (Wright Cemetery 175)

The conclusion of the section devoted to “the fine arts” in the big Lincoln County History discusses two figures, the well known film maker Bennie Kemp and Albert A. Bass. In 1956, when Bass was 85 years old, he was lionized in the Stroud paper as a man of advanced years who “Still Foots His Own Bills.” He had just opened a portrait studio in Stroud and the paper commended him for his complete independence, noting that he had been a photographer since he was twenty-three yers old and tin-types were just going out of photographic fashion.

234

He says that it has been so far back [when he began] that he can’t remember why he chose photography. “Ever since I can remember, it has been in my blood,” he stated. . . . An amateur musician, Bass plays the cornet and snare drums. He has a beautiful tenor voice and sings with the first Methodist church here.

What about the future? “As long as my health permits, I’ll make my own way,” says the silver-haired, well-groomed gentleman. “And the only way I know is photography.”

Bass may not have taken the photograph at Oak Grove, but the probability exists. If so, the integrity and dedication of his life, give the picture a special luminosity.

To return to the Oak Grove photo, the smaller boy in the back left is C. R. Miller, later County Commissioner of Lincoln County in the early 1960s and thus familiar to Chandlerites. I went to high school with his younger son Bobby and later worked on Chandler’s City Crew two summers with Bobby and the older son Jerry repairing streets and water lines. They were both reputed to have rough ways, but I never saw anything of it. What I remember most clearly about them is that when it came to hard work, they were demons of readiness and willingness. C. R. died and was buried in Pleasant Ridge Cemetery in 1976, where his sons later joined him.

The central figure in the back and wearing an incongruous bow tie is Archie Pounds. He and C. R. Miller were close friends during their boyhood and youth, before adulthood pulled them in different directions. In the late 40’s and again in the mid 50s, Archie lived in northern California. He returned to Chandler in the late 50s and worked for a couple of automobile agencies in town before moving to Duncan to sell oil trucks. He retired in Chandler,

235

but later moved to Tulsa, where he died in 2004. He is buried in Chandler’s Oak Park Cemetery.

To Archie’s left is Ruth Smith, who married Leroy Reed and moved to Slidel, Louisiana. They had two children that are known, Earl and Cheryl. Leroy Reed died in 1997, and Ruth in 2014. They are both buried in Davenport Cemetery. A niece who is a member of FaceBook wrote to me that her Aunt Ruth “had a wicked sense of humor! Kind of on the sarcastic side. I remember [her daughter] Cheryl made her [mother] a memory book and she carried it everywhere she went and looked in it quite frequently.” The wicked sense of humor shows in the sly intelligence of her face and its hint of mischief. It’s a face that doesn’t declare what it knows.

The remaining male student is as yet unidentified.

Fittingly, the queen of this small group in the 1933 photo is the teacher, Daisy Palmer. Her brother Lee wrote the article on the Palmer family which appears in the Lincoln County Oklahoma History (Lee was also a teacher for a while). There we can learn the whole history of the family. Lee and Daisy’s father was Samuel Palmer, born in Crawford County MO in 1866. In 1891 he married Rachel Housewright, also a native Missourian, and together they had eight children.

Lee writes, "In the year 1902 the Palmer family

moved to OK, renting a farm in the Oak Grove School

District No. 47 about eight miles northwest of

Chandler" (LCOH p1136). Thus Sam Palmer was not a

homesteader but even so he was among the early settlers in

that area, and their proximity to Oak Grove school house

made it convenient for his daughter to teach there.

Speaking of the schoolhouse, Archie once told me, “Yeah, I

graduated out of the eighth grade right there, under Daisy

236

Palmer. The Palmers was old early-day settlers, lived a mile north and a mile west. The Palmers,

The ten Palmers at home near Oak Grove School about 1910.

the Gobles, the Littlebridges, the Stinsons, the Millers all settled in here in the land run” (North of Deep Fork 233-34), Archie is mistaken about the Palmers settling in the land run of 1889, but born in 1918 the mistake is a natural one for him to make. In his day, when a family lived on a farm long enough, it became known among themselves as “the old home place” and to non-family as the such-and-such place, no matter who the original homesteader was.

Lee continues the Palmer story:

In 1906 Sam bought an 80 acre farm about 3/4

miles to the north, which became our "Home Place" until sold in 1965. We moved into a 12 by 16 foot log house where Daisy and Zelphia were born. For a short time our entire family of ten lived in this log

house. . . . . I taught school at Banner, and Stone. worked at the North Cotton Gin for D. R. Owens, Deputy County Treasurer under Floyd Sodestrom. Managed the Southland Cotton Gin at Carney, manager

237

of the Hudson Houston Lumber Yard at Chandler and had the "Palmer Auto Store" in Pawnee.

What Lee writes of himself is interesting enough, but it didn’t make the local newspapers. The hunger for local news, which was always present, had a tendency to focus on the doings of girls and young women from the time they were about twelve until they got married. It’s a curious fact of newspaper reporting in rural areas during the first half of the twentieth century, that the doings of young women were closely followed in the social columns. A given area would usually have its own column in the paper, sometimes with the author writing under a nom de plume. In Daisy Palmer’s girlhood, these columns make plain, it was the daughters of the homesteaders mentioned above who were her friends.

We may glance at some of Daisy’s doings between 1917, when she was ten years old, and her teaching years beginning a decade later. She is first noticed by the “In and Around Carney” column of The Lincoln County News in January 1917. There we learn that “Misses Sadie and Daisy Palmer were Sunday guests of Miss Lonnie Delphon.” Such visits back and forth were recorded on the average of two to three a week, usually in the “Oak Grove” column, until Ms. Palmer’s teaching career began and she married in 1935. Among her best friends were Lonnie Delphon, Fredia Edgar, and Hilda and Grace Goble. A summary of names is provided by the report of an entertainment at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Herb Sprague in June of 1921:

Present were Miss Zelma Davenport, Gladys Bolen, Grace Goble, Lennie Delphon, Sadie Palmer, Dewdrop Shaver, Hilda Goble, Gredia, Edgar, Thelma and Thelda Miller, Moscow and Fred Shaver, Cecil Gladen,

238

Talmadge Davenport, Navy Styce, and Mrs. Anna Shaver and children. All had a fine time.

In April and May of 1921, we find Daisy giving reports for the County Extension Work. The earlier one was called “Pest destruction--the cutworm.” The later one had a more suggestive topic: “Why the Girl Left the Farm.”

At some time in this period, evidently while still staying with her parents, Daisy completed high school in Carney, which would have qualified her as a teacher for the primary grades (elementary school). Chandler also had a normal school (as mentioned by Lee Palmer below) from 1907 to the early 1920s. Daisy is reported teaching in The Kendrick News for September 1930: “Parkland school was out Friday. All the children were treated to Eskimo pies Thursday by their teachers, Laural Gower and Daisy Palmer.” Her brother Lee, in the article cited above, gives an overview of her teaching career:

Daisy taught school at Stone, Parkland, Oak Grove and in Illinois. She worked for the Welfare Department in Lincoln and Payne Counties and was a volunteer at the Stillwater Medical Center. . . . . All of the eight Palmer children attended the Oak Grove School. Daisy and I were graduates of Carney High School. Ruth took Normal Training in Chandler, and was going to teach school but her ambition was denied by death from typhoid in 1911. (Lee Palmer, “Palmer Family”)

References to Daisy teaching in all these schools have not been found but old newspaper archives are usually not complete. No reason exists to doubt Lee Palmer’s statement.

239

We may, however, wish to supplement it. Daisy’s 1940 census states that she has had two years of college, and this coincides with a letter she wrote in 1933 on stationary from Central State Teachers College in Edmond, in which she mentions her upcoming examinations. The letter is written to Archie Pounds to encourage him to continue his education by going to high school.

In its entirety, the letter reads as follows:

July 15, 1933

Dear Archie

At last I have found time to write you a few

lines. We have been very busy this summer. It is nearly over so I have that to be thankful for. I have all my outside work finished. Just waiting for the final tests. We take them Tues. and Wed. I am coming home Wed. evening and teach school Thurs. and Fri.

Have you been working hard this summer? It has been almost too hot and dry to do anything.

It won’t be long until you start to high school. I was so pleased to hear that you were transferred

Now, don’t get discouraged and quit. You are capable of making good grades in high school. I want to see all your names on the list of seniors four years from now. You will like high school after you get started and get interested.

I am sending you this picture as a token of remembrance.

Yours truly, Daisy Palmer

Here is a scan of the last part of the letter in order to display Daisy’s handwriting.

240

She knows how to loop some pretty loops. Wiki provides some background:

The Palmer Method of penmanship instruction was developed and promoted by Austin Palmer in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was largely created as a simplified style of the "Spencerian Method", which had been the major standardized system of handwriting since the 1840s. The Palmer Method soon became the most popular handwriting system in the United States. Under the method, students were taught to adopt a

241

uniform system of cursive writing with rhythmic motions.

Wiki misses the major contrast here. Austin Palmer’s method employed the arm, whereas earlier styles--and this was the source of their difficulty--relied entirely on the fingers, which easily tired or cramped. Palmer students first practice writing loops, whole pages with nothing but loops, trying to make them uniform in size and angle of slant. Earlier handwriting styles began with the students learning to print. Palmer’s method introduced them in their formative years to the writing style we call cursive.

Sometime in the 1990s, Daisy’s student Archie Pounds wrote to me about the Palmer method as follows:

I know you won’t be surprised at me writing to you because you know that I write a good hand. I always have. I was taught with the Palmer method, and as a boy in school I practiced those loops hour after hour. The funny thing is that my teacher was named Daisy Palmer.

Where I went to school there at Oak Grove was a one-room schoolhouse, so she was my teacher for a year or two before I started riding the schoolbus to Chandler highschool. She was always careful to explain to us that she was no kin to Austin Palmer, the man who invented this hand back in the nineteenth century. I still enjoy seeing it, though it’s mostly disappeared now, along with the style of teaching, though they’ve kept it in the Coca-Cola logo and one of the Ford logos.

I enjoy writing it, the familiar rhythm of the arm motion. That was the thing about the Palmer method, you see. Earlier penmanship had concentrated on the fingers. You wrote with your fingers, and they would

242

soon get tired. But with the Palmer method you put your whole arm into it, so your fingers didn’t tire. That was the way Miz Palmer explained it to me once. 7

To discuss Daisy’s letter only in terms of its handwriting, however, is to focus on style to the exclusion of substance. What the letter states is more important than its penmanship. In the last paragraph she is encouraging her student to continue his education. This was not an easy matter for pupils living around Oak Grove, for it involved two major shifts. First, they had to ride the school bus to Chandler, meaning that they would be later returning home to help with the chores than when they attended the country school. Secondly, the students had to learn to get along with “town kids,” who with the usual human talent for hierarchical distinctions and disfunction thought they were superior to “country kids.” Cases existed where 8th-graders graduated from Oak Grove chose to attend high school in Carney rather than Chandler in order to avoid town snobbery and to find compatible classmates.

In conclusion, however, what I’d like to focus on is Ms. Palmer’s encouragement of her student Archie. He attended Carney high school for a year or two but finally transferred to Chandler High School and graduated in 1937or 1938. Archie was the first person in his family to graduate from high school. His wife-to-be Opal Earl was one year behind him, and they married in Chandler in 1940. If Archie was the first in his family to graduate from high school, his daughter was the first in his family to graduate from college, and his younger son not only graduated from college about the same time as his sister but later completed a Ph.D. Which explains the opening paragraph’s reference to the long reach of a teacher’s influence.

7. Archie’s original letter is lost. What I provide is a paraphrase. 243

Years later in stories he told his children Archie liked to say that he wanted to go to college and study history but marriage and the birth of a child canceled any opportunity he may have had. Even so, he did become a historian in a small way. He kept documents from his childhood in what he called his “pretty box” (an expression he learned from his Appalachian mother meaning a box for his pretties), beginning with first-year valentines and ending soon after the 1933 8th grade graduation photo and the letter from Daisy Palmer reproduced in the present essay. A “pretty box” is a child’s attempt at building what scholars call an archive, and clearly the writer of the present essay has benefited from Archie’s archive.

A word about Archie’s wife Opal Earp will bring us to a final photograph. Her great grandfather was the Reverend Martin Van Buren Wright (1837-1914), buried in Black Cemetery northwest of Stroud. He’d arrived in the

Stroud area about 1893 from Boone County Nebraska, where the family home was graced with a photo by the noted Nebraskan photographer Solomon Butcher. If Opal

244

had been an archivist, we might have a better print than the one below, in which it is impossible to make out faces. The largest presence in the photo is the windmill whose indispensable role was to provide water for the family, the livestock, and the garden. The “autobiography” of Martin Wright’s daughter Mary Frances Earp states:

Over there they had a man named Solomon butcher, a dreamer who could’t make a living but he took splendid pictures of what he called “farm views” and I saw them in Stroud when his book came out about 1900. A few years after that, I mean, one of our church friends had it and loaned it to me to look at. It was called The Pioneer History of Custer County Nebraska. the pictures in my own mind had begun to fade until I saw Mr. Butcher’s. By the time we left Nebraska, in fact well before, I’d had a bellyful of sod houses and was glad to turn my back on them, but I found myself looking back at them with interest, now that we didn’t have to live in one. Hindsight is like that, you know, it has a sweetness now-sight never has. What I liked best in Mr. Butcher’s book was that he didn’t take pictures of people so you saw them close up. He showed the folks on the homestead in the way they lived with the land behind them and their precious possessions all out in front of them as if the chairs and dressers too were posing for the picture. (Autobiography 89).

Dying poor and unknown, Solomon Butcher was long remembered as a dreamer, a man whose reach exceeded his grasp.

With the comment from Mary Frances Earp above, the present essay stumbles to a close. The author had thought he might link the end and the beginning through

245

the two principal photographs, one from Archie Pounds and one from his wife Opal Earp, but it now seems too much of a stretch. I can only update the pronouns of Jesus ben Sirach and say: "Let us now praise famous men and women, and the parents that begat us." Which will allow Daisy Palmer to be included in the praise.

Sources

Apart from the items listed below, the data in this essay comes from the census records and vital statistics available at Ancestry.com, and from the Bureau of Land Management.

Palmer, Lee. “Samuel Louis Palmer Family.” Lincoln County Oklahoma History. Comp. and ed. by the Lincoln County Historical Society. Claremore OK: Country Lane Press, 1988, pp. 1136-37.

Pounds, Wayne. The Autobiography of Mary Frances Earp: Memories, Reflections, Dreams, 1862-1961. Columbia SC: Kindle Books, 2018.

-

_____. North of Deep Fork: An Oklahoma Farm Family in Hard Times. Charleston SC: Kindle Books, 2011.

-

_____. Wright Cemetery: The Oldest in Chandler, Oklahoma. Middletown, DE: 2020.

Solomon Butcher, “Sylv Rawling House,” Custer Co. NE, 1886

Sources

Apart from the items listed below, the data in this essay comes from the census records and vital statistics available at Ancestry.com, and from the Bureau of Land Management.

Palmer, Lee. “Samuel Louis Palmer Family.” Lincoln County Oklahoma History. Comp. and ed. by the Lincoln County Historical Society. Claremore OK: Country Lane Press, 1988, pp. 1136-37.

Pounds, Wayne. The Autobiography of Mary Frances Earp: Memories, Reflections, Dreams, 1862-1961. Columbia SC: Kindle Books, 2018.

_____. North of Deep Fork: An Oklahoma Farm Family in Hard Times. Charleston SC: Kindle Books, 2011.

_____. Wright Cemetery: The Oldest in Chandler, Oklahoma. Middletown, DE: 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment